Edge Magazine goes behind-the-scenes with Hypixel Studios, the developer behind the hugely anticipated Hytale

What happens when the announcement trailer for your indie game gets 54 million views – and counting? Well, first, your website has a minor meltdown. “There was a moment when the countdown hit zero, and the website script didn’t just quite perfectly fire,” project lead Aaron ‘Noxy’ Donaghey recalls. Everyone on the Hytale team, spread all across the world and gathered on Teamspeak for the occasion, held their breath for a good few seconds. Then the network team sprang into action to fix the issue. “And there was an inhalation – we watched the trailer once, and nothing was happening for like, the first two minutes.” But, as people started to finish the video, comment after comment after comment appeared underneath it. The reaction videos started rolling in ten minutes later. “It was…” Donaghey exhales. “Euphoric is an understatement.”

His fear was that Hytale – a game with more than a passing resemblance to Minecraft, created by many people with a background in running a successful Minecraft server – would be dismissed as yet another title destined for the ever-growing blockgame graveyard. But the trailer – which showed off features such as a realistically lit and animated world, adventure and minigame modes, extensive modding, an in-game animation tool and even live scripting – immediately struck a chord. “We had an internal poll on how many views,” Donaghey says. “In my head, you know, anything below 250,000, I’m disappointed. 500,000, I’m happy, and a million, I’m like, super happy.” At the end of the first week, the trailer hit 11 million views. The eyes of thousands of players, and some of the biggest players in the game industry, are now very much upon the project he’s leading. “I don’t want to come across like, ‘Oh, we’re burdened with all this interest’,” he laughs. “But it does change things. It undeniably changes things.”

Before Hytale, there was Hypixel. Started by Simon Collins-Laflamme and Philippe Touchette, it was one of the many fan-made Minecraft servers that popped up in 2013. Players were getting very good at using Minecraft’s creation tools – most often redstone, the game’s simplified version of electronics – to build complicated contraptions and incorporate them into ‘adventure maps’, focused campaigns that others could download and play, provided they had the technical know-how to get it running. Many did not: the process of hunting for hidden folders, ensuring the server config was working, and that your chosen mod was compatible with the version of the game you were using as well as the client you were using it with, was a headache. And so Collins-Laflamme and Touchette decided to run a server that would function as a playable library of all their adventure maps, where players could simply join the server to access a suite of games.

It quickly became popular. There were sometimes hundreds of people queuing in the lobby waiting for their adventure to begin. It was chaos. The solution? Introduce short, entertaining minigames to keep people occupied: snowball fights, or Quake homages, or even a curious thing called ‘Hunger Games’, inspired by a new film series, where you’d battle to be the last player standing in an ever-shrinking arena. Unsurprisingly, in hindsight, these short, fast, rewarding and even social minigames soon became the main draw of the server. Indeed, it drew in Donaghey, too: an indie developer and a Minecraft player since beta, a kind of server-slash-social experiment called CivCraft “opened my eyes to the possibilities of things that could be done in Minecraft”. He ended up getting a job at game server host Multiplay helping with customer support as, in his words, “the Minecraft guy at the company”.

Part of the job was attending conferences such as Minecraft Expo, which was part of Insomnia Gaming Festival. It was here that he met the Hypixel team. “They’re like, ‘Yeah, we’ve got 20,000 users’,” Donaghey says. “I say, ‘Oh wow, you’ve got 20,000 users so far.’ They’re like, ‘No, we’ve got 20,000 users online right now.’ I’m like, ‘What?'” he laughs. “It’s not every day you come across some people who have something that’s really special, who maybe don’t actually understand it at that point.” Already part of the way into the interview process for a job at Riot Games, Donaghey asked whether he could help out on Hypixel in the interim. “And during those nine months, I just completely fell in love with the team, I fell in love with the project, I fell in love with the community.” The work, which saw the team spinning up fresh minigames in sometimes as little as a week (SkyWars, one of its most popular, took six days to make, and almost immediately drew in millions of players), was fast-paced and creatively fulfilling. And the server was making good money from its microtransactions, too. The income was more than enough to sustain the server, and a team of around 40 people.

And then, the EULA happened. Mojang, in a bid to reduce the amount of bad actors using the Minecraft platform for nefarious means (including paid DDoS attacks, of which the Mirai botnet was perhaps the most notorious example), introduced new commercial rules for Minecraft servers. These put paid to many of Hypixel’s monetisation strategies. “There was still monetisation within the cosmetics scope of things,” Donaghey explains. “But that inherently comes with cost, right? I mean, it’s not the coolest thing in the world to say, but it is easier to monetise something by changing a variable. And what we were doing was saying, ‘Hey, we’ll give you double coins for life if you give us ten bucks’.” In a post-EULA world, this was simply not going to fly. Donaghey’s job, before he left for his new job at Riot, was to prepare Hypixel and its play rewards for the new era.

The server survived, but its revenue dropped a staggering 85 per cent. And suddenly, the team had to rethink how they were going to fund a platform that tens of thousands of players logged into every day. Donaghey and Collins-Laflamme continued to correspond, with the latter asking the former if he was interested in coming back to further help Hypixel get back on track.

“And I said I really wanted to, but I couldn’t commit to work on a company that – and it sounds a little bit extreme for me to say – that I didn’t really see as having a future. Not because I didn’t think that the company could float itself and get by, but for me, it was like, if your future is going to be just being a Minecraft server, it’s probably not that sustainable for me as a person.” But Collins-Laflamme had never made a game before, “and I had the whopping experience of two indie projects under my belt,” Donaghey jokes. He suggested they’d need about seven people, 18 months, and $700,000 to make their game. “And he said, ‘Okay’.”

The one thing they definitely didn’t want to do was make a blockgame. “Every single fibre of our bodies was like, ‘No, don’t make a blockgame!'” Donaghey laughs. “‘Let’s make a 2D top-down shooter!’, you know.” This seems faintly unbelievable considering the current reality of Hytale, which has been nicknamed ‘Minecraft 2.0’ by legions of excited fans: it looks for all the world like a calculated run at making a deliciously profitable sequel to one of the biggest games of all time. But Donaghey’s explanation of the Hypixel team’s reluctance rings true.

“I think it was pride – I don’t mean to say that we’re too proud to make Minecraft. But we were very much in the nest. And when you want to leave the nest, you want to get as far away from the nest as possible, right?” And so some of the world’s most talented Minecraft modders started noodling around with some concepts for non-Minecraft games, while still playing hours of crafting games such as Terraria. “The realisation just sort of hit us – why are we fighting something that is just our nature? Like, our nature is that we want to go and make something for this community that we know, and we understand, and we appreciate and that we really treasure. And we’ve got the world’s best team to actually make something that can move that genre forward.”

So they started making a blockgame. And if they were going to make a blockgame, it would have to be more focused on community empowerment than any other of its kind. It would have to do what Minecraft couldn’t, or wouldn’t, purposefully offering its community the hyper-flexibility it was attempting to wring out of such games. While other challengers to Minecraft’s throne have built their efforts in Unity or Unreal, the team at Hypixel knew from their wealth of experience wrestling with Minecraft’s back end that there wasn’t an engine in existence that could handle the complexities of the voxel-game-slash-platform they wanted to make.

There was nothing that could handle the chunk meshing and loading that Hytale’s procedurally generated world ‘zone’ system relies on to create detailed worlds for players to explore. And so they would have to code an engine from scratch. “I wish we had known how hard that would be,” Donaghey says. “But if we did, Hytale wouldn’t exist. If we had known that this would be the path that we would take and it would be this hard, we wouldn’t have got there. But that optimistic kind of ignorance ended up being like one of our best weapons. And now it’s like, okay, so we managed to be the one out of 100, or the one out of 50 that made it through that process. Now we’ve got to actually make the rest of it.”

It is dusk in Hytale, peaceful and purple and quiet, save for the chirps of crickets all around. As we marvel at the long grass around our camp swaying in the breeze, and watch a flock of birds rush overhead, rain begins to fall. Procedurally generated hills and plateaus composed of cubes rise up around us. Content lead Sean McCafferty – whose ginger-mohawked character moves in a much more realistic manner than his Minecraft predecessors ever did – starts walking us through the game’s crafting loop: a fieldcraft system allows us to make basic survival tools on the go, including a workbench that gives us access to more complicated crafting recipes. Digging reveals a procedurally generated cave system peppered with curious vegetation and stalactites. It’s also riddled with marauding goblins, who are then dispatched with a few swings of a particularly vicious-looking sword or – more unusually – a well-aimed blast from a magical staff. So far, so Minecraft, then – perhaps if you’d managed to load it up with a slew of fancy shaders and some animation mods.

As time goes on, however, the high-level differences become apparent. A short way over to the east, we happen across a charming little shack – and then, further on, a ruined fort. It’s guarded by a couple of bobble- headed skeletons, and there’s a river running into its basement, creating a kind of half-sunken treasure room. “The prefab you saw on the left-hand side, that singular building – that is probably set up exactly the same way as this more complicated one,” McCafferty tells us. “It’s just chance what happened. Like this one –” he gestures to the small building – “just had one node, the ‘parent’. Whereas this one –” he hops towards the fort – “had many, many children. So basically you’ll have a centrepiece or you’ll have a primary part of the puzzle, right? And it may or may not spawn children, and those children will be attached.”

There are around 7,000 prefabs currently in the game, he tells us, and each “zone” of the map will have its own sets of rooms, dungeon entrances and so on, but each one those will have multiple variations that could be generated. (Hytale’s maps are procedurally generated, but always follow a rough structure: the more temperate Zone 1 in the middle, the hot jungle and dry deserts of Zone 2 to the south, and the frozen Zone 3 to the north. The climates of each zone also get more intense the further into them that you trek, and the difficulty of missions and their rewards ever greater.)

It’s an encounter in itself, with foes to fight and treasure to plunder – the run-down appearance of the building indicating a lower-tier enemy difficulty level. A surprisingly beautiful ruined cottage elsewhere catches our eye as a potential renovation project. But prefabs can also be tied to specific, geographically located objectives – for instance, the ‘tier-two’ tower we run across next, a cathedral-like structure that easily dwarfs any building we’ve seen generated in Minecraft. These tower encounters pop up in each zone, but each is themed differently (this particular one represents the element of earth that Zone 1 centres around) and is accompanied by pop-ups that explain your mission, and how it relates to the part of the world you’re completing it in. If it’s a Trork camp (one of Hytale’s more hostile races), you might be told to destroy ten Trorks, or rescue a peaceful Kweebec hostage.

You might also be given a treasure map by a vendor, or a bounty quest, where you track an enemy and destroy it for a reward. Combat, too, aims to be a cut above most other blockgames. “We come from a minigame background, and PvP is a big, big part of that,” McCafferty says. “It’s not just about this act of swinging a sword: blockgame PvP is about much more than that. It’s about people who can place blocks at lightning speed – like, you can have a guy coming towards you with better armour and better gear, and you can block yourself backwards across a void and then start hammering blocks he’s walking on to make him fall… What we want to do is take the onus off the ‘spam clicking’ sort of behaviour , and give us a little bit more depth.”

Combat in Hytale – with the help of slick animations – will revolve around being reactive and proactive, letting players make use of charge attacks, dashing, blocking and “maybe even sneak attacks”, we’re told. Weapons in Hytale are broken up into families, with each having their own particular attack pattern to master: one-handed swords, two-handed longswords, warhammers that have a slower, wide-sweeping attack for crowd control against weaker enemies, and axes that have a limited range of motion but whose vertical chops deal devastating damage.

Now free from the restrictions that someone else’s game and engine imposed upon them, the team at Hypixel Studios have just kept going, and going. We’re shown modular dungeons, both overground and underground, which are signalled by gigantic doors and will be filled with loot and boss rooms. While spelunking, we run into a treasure room, in which a miffed treasure goblin chases a mildly panicked McCafferty. In Zone 2, mist creeps over a crop of hot springs near to a settlement filled with people of a fox race known as the Feran. Unlike the friendly Kweebec, we have to work a little harder to build goodwill: our standing with them is currently neutral, but we’ll be able to offer gifts of meat or make offerings to their gods to gain standing with them. (Still, the Kweebec are no pushovers: “If you start butchering their children, they call these guys called the Razorleaf Rangers, who are hard as nuts,” McCafferty laughs.)

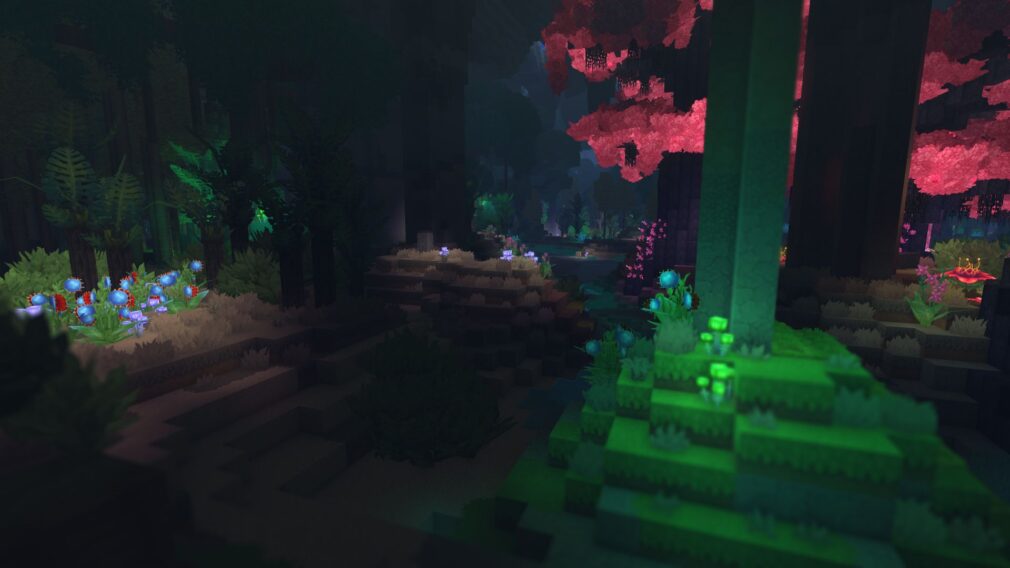

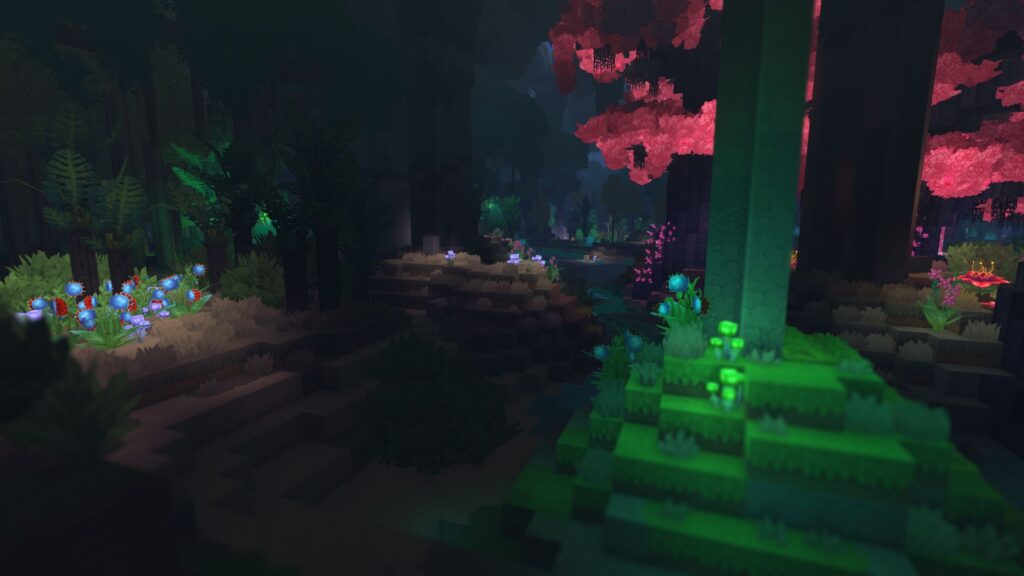

In the icy boreal wastes of Zone 3, we meet yet another NPC faction, the Outlanders, who perform mysterious rituals under cover of darkness. Gigantic glaciers cast hulking shadows across snow-dusted dirt; a yeti shuffles about in the distance. Later, we get a brief glimpse of an intimidatingly large ‘stone circle’ in the later-game Zone 4, which is flanked all around its edges by viscous, glowing waterfalls of lava. As an important part of Hytale’s narrative, there’s guaranteed to be a stone circle in every zone: this one, representing the fire element, almost looks like a giant, jagged crown, and is surrounded by burning trees. Ashfall flutters to the ground all around. And then we’re shown what’s underneath Zone 4: a whole other zone, a subterranean jungle filled with lush, bioluminescent flora through which dinosaurs roam freely.

And all this is before we even get into the potential for player-created content: Hytale is, after all, intended to be as much a platform as it is a game. Publishing lead (and former Edge contributor) Chris Thursten brings up the asset editor. “So this is a kind of a modding interface, functionally, or customisation interface that touches almost every aspect of the game,” he says, “and it can be used on the fly to change a hell of a lot of things.” He equips his character with a cobalt sword and shield; the interface brings up all the information we could possibly care to know about the model, including its size, what particle effects it uses, what models it uses, how it’s crafted and what resources it requires. You’re then able to alter it in a dizzying variety of ways to best fit the type of game experience you want to have on your Hytale server. “That’s just a really basic example.”

Things get slightly more complicated when Thursten turns into a pigeon. This, McCafferty tells us as Thursten tweaks his character model to show us its shape, hitbox, animations and even the camera angle attached to it, is a fairly standard occurrence in the Hytale devs’ games. The final touch is an iron dagger tucked under one wing – and absolutely usable in combat. “Any of the weapons should work with any of the characters,” McCafferty explains: the studio has a naming convention – the pigeon’s wings are labelled as ‘arms’ – which lets the game share animations across different models so that they’ll work decently in just their standard form. “So if you want to make a custom server for you and your friends, or a minigame, where everyone is a bear,” Thursten says, “that is fine.”

And it goes further than simply swapping assets in and out: machinima creators will be pleased to learn that you can control the weather and time of day through the interface, so that nature doesn’t cause continuity errors on shoots. We’re shown a swatch that allows players to establish the colour-grading to the sky for the perfect sunset, and a feature that establishes what PNG file is used for the moon, or the patterning and colouration that’s used for the clouds. We watch as Thursten checks a box to relocate the ashfall weather we saw earlier in Zone 4 into the leafy, temperate Zone 1, then tweaks the parameters and the ordering of combat sequences for a mace.

And, provided they have permissions from a server’s owner, players can do it all without having to reload the game. McCafferty changes a grass texture on his computer via the asset editor, and sure enough, the new texture appears on our screen just a few seconds later. “What this means functionally,” Thursten explains, “is that there’s no sending files between modders as they work on a custom game.” Alongside Hytale Model Maker – which is essentially Google Docs for asset creation, letting one creator work on, say, the animation for a model while another on the other side of the world paints its face – it’s clear that Hytale is more than a blockgame. This is a formidable suite of tools that makes incredibly advanced in-game creative collaboration possible in realtime, and will, with the help of a dedicated community, produce results even Minecraft daren’t dream of.

It’s taken three years of work, in secret, with a team spread across the UK and Ireland, Canada, France, Russia, Australia and more, while a separate Hypixel team continued to run the Minecraft server. A good chunk of that time, Donaghey tells us, was simply wrestling with and iterating on “the idea of genre versus games. When you look at a genre – say, first-person shooters – there are certain things that are definably genre, and there are certain things that are definably the game.” He points to the R key on a keyboard being ‘reload’ for both Call Of Duty games and Borderlands games. “You’ll always have these, like, inherent behaviours that you expect, but what’s really fascinating is because there’s only one incumbent in the genre, and there only ever has been one incumbent in the genre, sometimes it’s not super-clear on what the differences between genre and game are. And what we really want is – despite being a Minecraft challenger – we don’t want people to think that we’re like, building Minecraft 2.”

The desire to express Hytale’s differences – a greater amount of overworld content, rather than hiding almost everything in underground caves; a focus on giving the community access to powerful creation tools from the get-go – manifested in one particular idea. The first thing that would happen in Hytale, the team decided, was that a player would spawn in front of a tree. Blockgames being blockgames, they would then punch the tree, expecting it to break into craftable material. Instead, their character would say, ‘Ow’. “And I thought that was like, the smartest thing ever,” Donaghey laughs. “We’ve shown the player not to expect Minecraft. And then you try that with someone, and they’re like, ‘You can’t do that!’ And this is a microcosm of a thousand smaller things that we have to decide every time: is this something that’s part of the genre, or something that’s part of the game? And we realised that the unique chance we have is that we actually get to kind of decide.”

And they had help. Rob Pardo, former chief creative officer at Blizzard, who eventually came aboard as one of Hytale’s investors, explained to Donaghey and co that being different for the sake of being different was not necessarily a good idea – better to simply add something more to the equation. ” For a lot of veteran game developers, that would seem like a relatively obvious thing – but for us, it was like, whoa.” Indeed, in 2016, while Donaghey was visiting LA for Minecon, he sent an instant message to his friend Mark Hillick, who works in infosec at Riot Games, asking if he could show someone at Riot a demo for Hytale.

He’d recognised a parallel between how they were moving from modding Minecraft to making Hytale, and League Of Legends being essentially the successor to Dota, and wanted to ask advice on “how to do that process respectfully. We didn’t want to annoy Microsoft or something. If you were to think of this in a bad way, it’s like, ‘Hey, we’re taking our football, and we’re leaving!'” Hillick ended up pitching Hytale to someone at Riot while on their campus for a fitness workshop. “And he’s basically doing a wheelbarrow with this senior person,” Donaghey laughs, “and he’s pitching, ‘Hey, my friend’s in town and he’s working on this game, and he would love to talk to you.'”

Riot ended up being just one of the industry luminaries the Hytale team met with and gained insight – and later, investment – from. At first, their instinct was to reject the offers of financial support from a “super-angel-investor squad”, Rob Pardo, Dr Anthony Borquez of the University Of Southern California and Super League Gaming CEO Ann Hand among them. “They would ask questions like, ‘What does your cap table look like?’,” Donaghey says. “And I’m like, ‘What is a cap table?’ I thought it was like a chart of responsibilities, because people wear different caps at a company, you know! And it turned out that that meant, ‘What does your share structure look like?'” None of them felt ready to have any of these conversations – they were still finishing up their engine, and working on the fundamentals of the game. They didn’t know how to start thinking about big business.

And then, in April 2018, their hand was forced again. “There was this game, I don’t know if you’ve heard of it? It’s called Fortnite,” Donaghey jokes. And then, more seriously: “So that halved our player count. One half. In the space of like, two, three months.” The addition of a battle-royale mode had been so popular that it was having a tangible effect on the profitability of the Hypixel server – and, by extension, the future of Hytale. “That little comfortable pad that we had where we were making enough money with a Minecraft server to fund Hytale was suddenly like, boom, break even. It’s not that we weren’t confident in being able to continue, but we didn’t feel like we could safely rely on that.” They needed funding, and they’d written off the Kickstarter approach as irresponsible, given other games’ past failures to deliver, and the fact that the blockgame audience tends to skew younger. And so they went back to the investors they’d met in 2016 and said, yes please, if you wouldn’t mind. Incredibly, they closed the funding round the day before they published the announcement trailer.

After the trailer, Donaghey tells us, “all sorts of things that we hadn’t anticipated started to happen, on pretty much like day five, six, seven.” First, there were the emails: instead of one person every few weeks asking about working at the studio, Donaghey (and several other devs) were receiving 800 applications in the same time frame. Then there was the chaos caused by what Donaghey terms a kind of content-creator gold rush: “Some people were just assuming that, you know, we would be exactly like Minecraft, and do things exactly like that. And, like, a simple example of that was, you know, someone went out of their way to make, like, hytaleserverlist.com.” (Indeed, a quick Google shows multiple similar sites.) “‘And I have done that without talking to anybody, without their permission. I have built this huge, custom, bespoke server browser and poured my heart and soul into it.’ And then you’re like, hold on a second – we have a server browser in the game.”

Hyper-analysis began to appear, which was challenging to deal with. “Everyone knows the story of Jack and the magic beanstalk, right?” Donaghey says. “Where Jack brings a cow to the farmers’ market and someone says ‘Hey, I’ll give you this magic bean for the cow’. The thing that got Jack interested was the possibility – he imagined all the things this game could be, or this bean could be. It’s like a 360-degree rainbow of possibilities – and the reality is the actual thing that it becomes can only ever be XYZ slices of that rainbow. And what we’re trying to do is at least deliver enough of a rainbow that people can build the rest of it.

“Our mission statement is ‘the most empowered community in the world’,” he continues. “But no one ever became a modder without there being an audience. You know, Starcraft 2 has some of what I would say are the best modding tools in the world. But people didn’t mod for it that much, because the audience didn’t hang around to be modded for. So that is the scope of the launch deliverable: we must deliver something that will facilitate the community for long enough that they can then go and build their own stuff.” Last year, Hypixel Studios announced that Hytale would release in 2021, rather than the original estimate of 2019, to give the devs more time to execute on the scale required for Hytale to be the kind of platform it can be.

But there were huge benefits to that announcement trailer. Naturally, when your indie game gets 54 million views on YouTube, the biggest names in the game industry come calling. “Suddenly, like, we weren’t having to explain ourselves any more,” Donaghey says. “And it became a buffet of possibility. This person, from this company, wants to talk to you. And, you know, all of a sudden, ,your head is being split in every direction. And what’s really important is the community – as much as I really appreciate and respect all the interest we’re getting, they were effectively distractions. But we are…” Donaghey pauses. “Because we identified that we had to improve a level, we did know that we needed help. But suddenly, we were in this incredibly fortunate position of being able to choose what that right help was.”

Unsurprisingly, there have been business meetings galore about Hytale’s many possible futures. But there have also been encounters that, on a personal level, have put what the team are doing with Hytale in sharp perspective for Donaghey. “”You’re meeting people that, when I was 18, they were like, the absolute dream to work with. I remember I met this person just walking past at E3, someone introduced me really fast. He goes, ‘Oh, wow, you guys are from Hytale – we’re really paying attention to what you guys are doing.’ And this is the person that’s like in charge of, you know, Fortnite.” Considering the havoc Epic Games’ battle royale phenomenon wreaked on Hypixel’s Minecraft server, that must have been a particularly delicious moment for Donaghey. “But at the same time, it’s all kind of flimsy, right? Because unless you back it up by actually delivering something for that community, what’s it worth, really, in the end?”

He laughs, and apologises for sounding unappreciative. But that relentless focus on community empowerment is exactly what motivated Riot Games to invest in Hytale’s development. It, clearly, has put its money where its mouth is, trusting that Hypixel Studios can deliver. Having seen the demo, we’re inclined that way ourselves – but how does Donaghey feel, given the blockgame bodycount only ever seems to rise? “The word Minecraft-killer is the term we reject the most,” he says. “But we definitely are in that space, and when you say, ‘Well, what gives you that ability to compete in that space?’ It’s because we’re of that space. We’re grown from that space. And it’s a new space, right? To this day, there’s still only one de facto game in that space.

“The thing that I think ends up being the fundamental mistake that people make,” he continues, “is they look at the genre, and they look at Minecraft as a thing that you open and you play, you go and get your diamonds and you go through to The End. That game loop – that’s how they look at Minecraft, but that’s not what Minecraft is. That’s not what the genre is. The genre is what the community’s made it. And so with Hytale, the scope is that we have to deliver something that’s going to basically be applicable to that entire ecosystem at the same time. And that is where the challenge is. That’s what keeps me up at night.” What he’s trying to say, we suggest, is that while others adopted the blockgame, they were born in it – moulded by it. “It’s definitely a Bane origin story, yeah!” he laughs.

Our terrible jokes aside, that’s exactly why Hytale’s future looks so bright: this is a team with perhaps the best shot yet at giving their community exactly what it wants, because they’ve done it before to an unprecedented level of success. With world-beating blockgame experience, and the suggestion of more help to come in executing its vision, Hypixel Studios might just grow its magic beanstalk. “My dream is that one day I log on to the Hytale server, and I see this new spectrum of possibilities,” Donaghey says. “I can go through someone’s homebrew tabletop campaign, or an RPG that is like a sci-fi world, or inspired by Studio Ghibli. The dream is to push the blockgame genre forward; that is the de facto objective with the game. Our success goal is that Hypixel 2 comes from Hytale.” He laughs. “Maybe in ten years, you know, when we’re old and decrepit, we see a trailer online, and it’s like, ‘Hey, someone’s gonna take on Hytale.’ That would be the actual dream for us, right? That’s our success bar right there.”